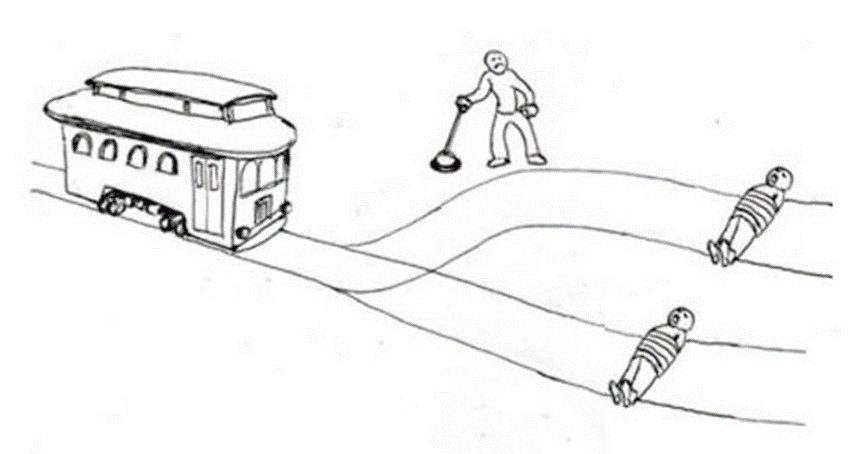

You have probably seen the runaway trolley problem. You know the one where a trolley (not a shopping trolley in fact, but a tram) is destined to kill X amount of people. You can pull a lever and save them all, but you will end up killing someone else. It is basically trying to summarise the debate between Utilitarians and Kant.

Here is an interesting variation that is perhaps not as well

known. Imagine the tram is heading towards one person, and you can pull a lever

and save them but it will also kill exactly one person. Do you pull the lever?

For utilitarian’s, it shouldn’t make any difference whether

you pull the lever or not as one life is equal to one life. For people who

follow Kant’s categorical imperative, by pulling the lever entails killing

someone and treating them as a means to an end. But by not pulling it, are you

not doing the same thing? It really all depends whether you view inaction as an

action in itself. Personally, I think it is.

In practise most people would feel more morally

culpable if they pulled the lever than if they did nothing. Now I am not

one of these people that bring up biases all the time, but I think this

particular bias is interesting. It is called, omission bias: the tendency to

view harmful actions worse than harmful inaction.

I think one reason we have this bias is partly to do with how

we view causality: if you do not intervene you can always tell yourself “it

would have happened anyway”. If you do intervene, however, you feel like you

have personally changed the course of history and so are more responsible.

As someone who thinks a lot about causality, I find this particularly

interesting. This is because most situations are not as clear cut as pulling a lever on a runaway trolley/tram. The future is uncertain and we don’t

really have a counterfactual to what happens in life. What makes matters worse

is we tend to judge decisions with the benefit of hindsight, rather than what was

known at the time.

And even though I know all this, if I were to ask my friend

to get me something from the shop on the other side of the road and she

subsequently got run over, I would be racked with guilt. Yet, if she just

decided to go to the shop on her own and she got run over, I would feel

extremely sad but I wouldn’t feel as guilty. It would have been odd for me to

say “No, don’t go to the shop, you might get run over”.

If you were to ask the average person on the (Western) street what the biggest military mistake over the last 50 years was I am pretty sure most people would say Iraq or Afghanistan. I think it would be quite odd if you heard someone mentioning Rwanda. Rwanda was a case where military intervention was decided against and the total resulting deaths were around 1 million people.

Now I am not trying to say that any of those decisions to go (or not go) to war

were right or wrong here, I am just wondering whether peoples responses to them have something

to do with omission bias.

I also think omission bias can help to explain a whole load

of other things, from decision to not vaccinate children to what Jeremy Drivers calls personal Cheems mindset– how we tend to favour inaction over action in our

everyday lives.