Right, I am not going to lie. To understand what happened last week is extremely difficult to explain as you need to understand a few things before we even get to fully understand what happened. By a few things, I mean you would have to learn half of my 2nd year economics undergrad course and even then it would be hard going.

Firstly, I think it is helpful to read about how interest rates are used to control the economy, managing the trade off between inflation and unemployment.

I then think it would be useful to understand what quantitative easing is and money creation in general but not as important.

These two things are hard enough as it is, before we get to the world of exchange rates and gilts.

Why do exchange rates move around in the first place? Well an exchange rate is simply the amount of one currency you would exchange for another. So at it's lowest last week, £1 would at point get you around $1.04. We tend to usually pay attention to this when we go on holiday. But primarily the exchange rate is important for trade and investment, it also works a lot like any other good.

Let's say pork pies become the must have global item and NY fashion models are demanding them on their riders along with champagne and caviar. As demand rises for pork pies from the US, they obviously can't pay the good people of Melton Mowbray in dollars, so they need to obtain pounds in order to pay for their gelatinous treat. As there is a fixed supply of pounds circulating, this leads to an increase in the price of the pound to dollars, this price is what we call the exchange rate.

What effects exchange rates frequently is interest rates. If the UK decided to raise interest rates, then people from abroad would want to take advantage of this higher rate and buy government bonds. There would be a demand for pounds which would increase the exchange rate and strengthen the pound.

In the UK, we call government bonds "gilts" (as a result of the paper contracts having a gilded edge, apparently). These usually work a lot like the fixed-term bonds you can take out with your bank. The longer the bond, the higher the interest rate you would get. The "yield spread" is an important indicator. It measures the pay-out difference between short-term bonds and long term-bonds. A higher spread indicates the investors are more concerned about the economy in the long-run, and makes it more expensive for the government to borrow.

Now some investors will want to buy and sell currency to take advantage of small differences in price. Let's say it was suddenly announced that unemployment in the US was lower than expected, immediately the dollar would rise. The reason being is that investors think it is more likely that interest rates will rise as a result (you should now understand this if you read the first link in this blog) and people from the UK will buy US government bonds.

But why don't investors just simply wait until the Federal Reserve (the name of the US central bank) actually announce an increase in rates? Well, this is because you can lose out.

Lets say the exchange rate of pounds to dollars is 1.20. We expect the pound would get weaker against the dollar if there were a rise in interest rates in the US. As demand for dollars rises, we may think the exchange rate will end up around 1.10 in the future. So if I buy it now, I get a better deal. I can get 10 cents more for every £ I buy then if I waited (I am buying at 1.20 then 1.10). But because all investors have the same idea, the exchange rate moves extremely quickly to this new exchange rate. This is because the faster you act, the better deal you can get as you can buy closer to the old exchange rate! This process is known as arbitrage.

Now of course this is just an expectation of the way, things work. It could turn out that interest rate rises don't actually happen in the US for various reason. The point is, these currency markets take into account future information as there is money to be made. When someone says something in the future is "price in", it means markets have already taken account of this and it is reflected in the price.

So why did the pound fall to the dollar in late September 2022? Well, trying to explain movements in the market is something we should be not overly confident about. It is quite complex to unravel everything even if the narrative sounds plausible. The first thing to note, that in the US interest rates are high and increasing, so there is already a lot of demand for dollars.

In the UK, the trajectory of interest rates also seems high. But should this not increase demand for pounds? What's more, when the chancellor announced his new tax plans wouldn't that also add a stimulus leading to inflation, hence making it more likely interest rates would increase. Wouldn't this make the pound stronger? The simple answer is, yes. This is what we should expect. However, the markets may have been concerned that these tax cuts were unsustainable as they would be paid for by borrowing.

This is something that George Osborne was worried about and subsequently imposed spending cuts as a result. (Although the macroeconomic conditions were very different 10 years ago - interest rates were extremely low to the extent it was causing a problem called the zero lower bound. Oddly this resulted in not borrowing when rates were low 10 years ago and borrowing when rates are high now. Yes, this is as bad as it sounds.).

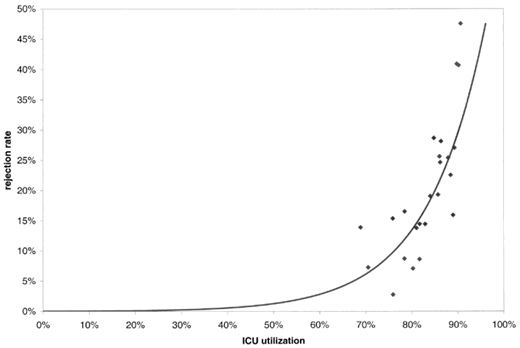

When debt is sufficiently high (and I am not sure we know how high really), markets worry that inflation will happen as a result and hence your returns are not as good, so many investors start selling off UK bonds which makes the pound weaker.

There is a strong possibility that this is what happened to the UK. This is something that usually happens in the emerging markets when governments make unfunded fiscal promises. This perhaps wasn't helped by the governments derision of independent bodies like the Bank of England or the OBR.

The government, however, disagree. They suggest their tax cuts are not inflationary (as in just increase demand) as they are designed to increase supply. If you increase the supply of something, you not only increase output, but you also lower the price. So supply-side policies will actually help with inflation as well as debt. This is because the economy will grow and you get more tax returns as a result. This why the government are so concerned with growth.

I actually think being concerned about growth and not just debt is a welcome move. However, I am somewhat sceptical that these can come from the tax cuts proposed, which I am also guessing the market also thought as well. I don't think they are evil or doing for their mates in the city (I wish I had friends like this). I think the government are genuine believers in supply-side logic, even if you think it is a totally mad thing to believe in.

If you have got to this point, well done. You can be rewarded by now trying to work out what happened with the pensions market, and why the Bank of England had to step in. Now, many people will say the Bank of England did QE in order to stabilise the market, but I think this is unhelpful. Especially because the Bank of England of course want to do the opposite at the moment, lower demand to control inflation. Yes, they did create money out of thin air but this is not really to increase demand. It was essentially to increase liquidity as the lender of last resort.

Liquidity is all about time. If you go to the shop and find out you have no money, you can't say to the shopkeep that you own a house so you are good for the money. You need cash to pay for it. So a liquidity problem is not necessarily about whether someone can afford it, but whether they have enough time to sell assets in something they can move on quickly like money. The more liquid something is, the more freely it moves (hence the name).

Now I must admit that I actually had no idea why the pension markets was going crazy. Higher interest rates should be good, as a lot of pensions invest in government bonds. The problem, as far as I understand it, was that pension investors "hedged" against interest rates rising so quickly. A hedge is a way of insuring yourself against something happening, hence the phrase hedging your bets. For reasons, I am not au fait with (finance is boring), this created a liquidity problem. If the Bank of England failed to act, a financial crisis was well on the cards and deep recession would follow.

Anyway, I hope this blog has made things a little clearer. But I can totally understand if you want to never think about these things ever again.